- Home

- Drosso, Anne-Marie;

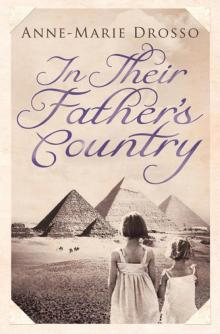

In Their Father's Country

In Their Father's Country Read online

Anne-Marie Drosso

In Their Father’s Country

TELEGRAM

eISBN: 978-1-84659-107-5

Copyright © Anne-Marie Drosso, 2009 and 2011

First published in 2009 by Telegram

This eBook edition published 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

TELEGRAM

26 Westbourne Grove, London W2 5RH

www.telegrambooks.com

1924: Selim

In the late afternoon of November 19, 1924, while Cairo nervously awaited the British response to the downtown shooting of Sir Lee Stack, Sirdar of the Egyptian army and Governor General of the Sudan, bedridden Selim Sahli was thinking of another shooting.

In 1921, during the Alexandria street riots over the British presence in Egypt, a policeman had killed a man watching the melee from a balcony. The victim’s family – Greek working class – had launched a lawsuit. The case had worked its way up to the mixed court of appeal, and was scheduled to be heard at the end of the month. An experienced lawyer, Selim accepted the case pro bono. He had already prepared his argument that the court’s reach extended to the policeman’s action for no arm of government should be above the rule of law. It would be a hard case to win, which made him all the keener to have a go at it. His head propped up by pillows of assorted sizes, he wondered whether he would have the strength, come the end of the month, to address the court.

Until the previous evening, he had assumed that he would. Now, after an especially difficult night and a heavy dose of painkillers, he felt almost as weak as he had in Paris after his last kidney operation. Reluctant to pass the file to his partner Mahmud Bey, who had two difficult cases of his own to argue, he decided to give himself another forty-eight hours before calling him. In the meantime, Selim would polish his submissions. The sight of the files stacked high on his bedside table invigorated him. Yet a shooting pain in his back stopped him from reaching for them. Losing heart, he remembered with exasperation Nietzsche portraying illness as a state conducive to fruitful contemplation. ‘Rubbish,’ he thought.

The curtains of his bedroom window were drawn back and the shutters pulled up. The windows themselves were opened just an inch, as he liked to hear the sounds of the city and feel connected to the hustle and bustle of the outside world. It kept his spirits up.

With its thick Persian rugs, Venetian lamps, canopy bed and walnut furniture, his bedroom bore all the signs of affluence. Yet, compared to other bourgeois Cairene bedrooms at that time, it was almost austere, lacking the usual profusion of ornamental objects. Though decorative, alabaster bookends on a small writing desk, and silver jewelry boxes on a dressing table served a utilitarian purpose. The fine white gauze curtains were not shiny satin; the one mirror in the room had a reddish oak frame with a matt finish, rather than a gilded frame. Black and white lithographs – mostly street scenes – covered half of one wall, while three large overfilled bookcases took up the entirety of another.

The apartment was within walking distance of Groppi’s, the Café Riche, Lemonia’s, the Muhammad Ali Club and Au Bouquiniste Oriental, all places Selim frequented but had not set foot in since the worsening of his kidney condition over two weeks ago.

A couple of minutes passed before the pain in his back diminished. Small as it was, this improvement made him euphoric and he thought again about his case until his two daughters, fifteen-year-old Gabrielle and fourteen-year-old Claire, came rushing into his room.

Gabrielle burst out loudly in French, the language she spoke with her parents: ‘Papa, Sir Lee Stack has been shot.’

‘Really?’ Selim asked, sitting up in his bed. ‘Really?’

‘Yes, yes. At lunchtime. In his car. On his way home from the war office, I think. Apparently, a group of young men standing on a kerb shot at his car as it slowed in traffic. His driver and aide-de-camp were hurt too. The three of them have been taken to the Anglo-American hospital,’ Gabrielle said, her voice rising in excitement.

‘Well, well ... ’ Selim said. ‘I must call Mahmud Bey. He might tell us more about it.’

‘What do you think this will mean for Egypt’s independence?’ Claire asked.

‘Not much in the long run. Trust me, Britain’s so-called special relationship with Egypt won’t last long. Egypt will sooner or later achieve total independence. Whether democracy takes root is another question though. Will Saad Zaghlul manage to steer the country in the right direction? Does he have the personality for it? One wonders. There seems to be a bit too much of the autocrat in him.’ After a brief pause, Selim went on, ‘Did I ever tell you that, years ago, I spent a couple of evenings discussing Rousseau with his brother Fathi who was in the midst of translating The Social Contract? Now Fathi Zaghlul had strong liberal instincts, even if he had some lapses – but then no one is free from contradictions. May he rest in peace.’

The two girls exchanged quick glances, taking it as a good sign that their father should be so talkative. He had been unusually subdued the previous evening. Their father’s precarious health had been a source of worry for them all their lives. He had sought treatment in Europe summer after summer. By now, they should have been inured to his bouts of illness. But since he rarely took to his bed, they were upset when he did. Their mother, herself very anxious, was incapable of providing the sort of reassurance that would have made the girls worry less about their father’s plight.

‘Papa,’ Claire asked, ‘why didn’t you ever become involved in politics?’ She recalled him supporting the 1919 lawyers’ strike and her mother’s concern when he took part in demonstrations. But why hadn’t he joined a party and become really involved? ‘After all,’ she said, ‘you’re for much of what the nationalists are for.’

Plump and balding, Selim had lively hazel eyes with a witty, attentive and kind expression. He put people at ease when he talked to them and made them feel that what they said mattered a great deal; because of this many found him handsome when he was actually quite plain. Even in his debilitated state he managed to look attentive. He took his time before answering.

‘The Syrians of Egypt are in an awkward position,’ Selim said, ‘so are the Greeks, the Lebanese, the Armenians, though we, the Syrians, are probably in the most awkward position. Is it our fault, for wanting to be all things to all people, or the fault of those among the nationalists who blow our distinctness out of proportion? A bit of both, I suppose.’

‘Papa, don’t tire yourself,’ Gabrielle said and looked at her sister disapprovingly.

‘Don’t worry. I’m feeling fine. It just occurred to me that you two might want to read Rousseau at some stage. It wouldn’t be a bad idea.’

‘And should we be reading Marx too?’ Claire asked. As a student, her father had returned from Paris with the first two volumes of Das Kapital in his trunk. His father would not have it in his household and had ordered his son to get rid of the books or not bother unpacking. Selim complied, leaving a note which read: ‘No to censorship!’ He was taken in by an accommodating aunt who suggested a compromise. Selim could go back home with his Das Kapit

al as long as he kept it out of his father’s sight, hidden somewhere in his room, and the father, pressured by his wife, had relented. This was what one of Claire’s uncles had told her.

‘Marx?’ their father said, ‘Marx too if you have the inclination. Read everything and anything, despite what the nuns tell you at school.’ Without a pause, he added cheerfully, ‘I suggest you now do something more useful with your time than keep me company, and I should try to do some work.’ Upon seeing his cook walk into the room carrying a tray, he said, ‘Ah! Here’s Osta Osman bringing me a camomile infusion. But where’s my mehalabeyah?’

‘Drinks first, food second,’ Osta Osman said beaming. ‘But more importantly, how does our Bey feel this afternoon? Much better it seems, thank God. Certainly better than last night.’ A big and bulky Nubian, who guessed he was fifty but was not sure, Osta Osman wore ample galabeyahs – always white and impeccably ironed – that made him look majestic. He had worked for Selim’s parents for many years and was considered part of the household. Though Middle Eastern dishes were his specialty, he could also cook French, Italian and even some German cuisine. The two other servants in the household – Om Batta, the washerwoman, and young Ali, the cleaner – were in awe of him and marched to his tune.

‘I’m upset with you,’ Selim said as he took the cup off the tray.

‘But why?’ Osta Osman asked, not seeming alarmed.

‘Because you didn’t tell me that the British Sirdar was shot. You must have heard about it soon after it happened.’

‘I didn’t want to interrupt your afternoon rest, my Bey. I was planning to tell you though. I gather that the young ladies have done that already.’

‘Yes, they have. So, what do you think?’

‘What can one say ... since the Dinshawai affair, things have gone from bad to worse for the British. It’s been almost twenty years but people have long memories. That several villagers were hanged, flogged, sentenced to hard labor for the death of one – only one – British officer after a fight which they, the British officers, caused, will never be forgotten or forgiven. I don’t need to tell you, my Bey, about the injustice of this sad story! What about the village women wounded by the British? And the young man beaten to death by them? All Egyptians were furious at the outcome of that trial – Muslims and Copts alike.’

In her heavily accented Arabic – unlike their father, both girls spoke it poorly – Gabrielle turned towards Osta Osman and said, ‘You’re right. I have a Coptic friend at school who gets very upset at the mention of Dinshawai.’

‘So she should,’ Osta Osman said. Looking at Selim, he asked, ‘What do you think Saad Zaghlul will do now?’

‘Well, the British will demand the usual. They’ll insist that Egypt forget about the Sudan, abandon any claim on it and withdraw its troops. That’s for sure. These demands will obviously be unacceptable to Zaghlul and the Wafd, so he’ll resign. Then the king will do his best to get one of his henchmen to be the next prime minister. He might succeed but it won’t last. As for those the police will arrest, one can only hope that these poor men will get fair trials.’ Selim winced and briefly closed his eyes.

Osta Osman promptly took the cup from him, saying, ‘What do we care about politics? It’s your health we care about. You have exhausted yourself with all this talk about politics. The doctor told us you needed plenty of rest. You look better today than you did yesterday, but I can tell you’re tired. You didn’t get much sleep last night.’

‘Neither did you,’ Selim said, in an appreciative tone. ‘There was no need for you to spend the night here. Madame Letitia overreacted. She shouldn’t have asked you to stay but you know how wives are.’

‘I would have stayed anyway. I intend to spend the night here until you feel absolutely fine.’

‘I had better get well soon then, before your wife and children start complaining.’

‘They’re quite all right without me. All they want is your good health.’

‘Your wife is very considerate,’ Selim said. He then reached for his files, though he did not open them.

Before leaving the room, Osta Osman said he would return with some mehalabeyah.

When Letitia Sahli, black rings around her eyes, woke her daughters the next day, it was dawn. She told them to come and see their father, saying tersely, ‘He’s not well. I’ll call the doctor although I’m not sure he’ll answer. I know he wakes up early but not this early.’

Shivering in their dressing gowns the girls hurried down the hallway, their mother behind them.

Sitting on a stool outside their father’s room with a heavy woolen scarf wrapped around his head, Osta Osman looked somber.

The girls tiptoed in.

Ashen-faced, his breathing labored, Selim saw his daughters nearing his bed and protested. ‘Mother shouldn’t have woken you up. It’s not an emergency. I’ll be feeling much better as soon as the medicine kicks in.’

He reached first for Gabrielle’s hand, then for Claire’s. ‘My darlings, your mother was right; seeing you I already feel better. It has been a bit rough but I’ll soon turn the corner.’ He pressed their hands and did look somewhat better. His breathing was easier, and his face had more color. The painkillers were finally having some effect. After a short pause he continued, ‘You ought to know though that, while children are indispensable to their parents, it is not the other way around. It’s one of those few situations in life where asymmetry makes sense, and is even desirable.’

Not knowing how to respond, the girls kept silent.

‘You’re much loved and cherished by your uncles and aunt. They’ll all be there for you, should – God forbid – something happen to me. As for you, my darlings, I know I can count on you to be good to your mother.’

‘Oh Papa, don’t say those sorts of things,’ Gabrielle cried out, holding back tears.

He pressed her hand. ‘Come, come, sweetie. I would be a negligent father if I did not tell you that, whatever happens to me, you have your own lives to live. I’m certain you’ll live them fully. Just make sure you don’t leave mother entirely to her own devices. You know her tendency is to isolate herself and withdraw.’

When Claire spoke, it was to say, ‘Papa, which one of Rousseau’s writings should we begin with?’

Her father looked delighted. ‘Rêveries du Promeneur Solitaire,’ he suggested.

‘Also, should I really try to sit for the bac? I’m tempted. Very tempted. I have been wondering whether to tell the nuns at school that I would like to give it a try. I’ll need you to talk to them, if they’re unwilling to help.’

‘But really Claire, now is not the time to saddle Father with this,’ Gabrielle said crossly.

‘Go for it,’ Selim told Claire, ‘so you’ll be the first girl in Cairo to graduate from a nuns’ school with the French baccalaureate.’ Then he turned towards Gabrielle and said, ‘It’s too bad we didn’t think of it earlier. It’s too late for you to get the ball rolling, but I have no doubts whatsoever that you would have done very well in the bac.’

He released their hands and closed his eyes. Every now and then, he would twitch, and one of the girls – by now both were sitting on his bed – would ask, ‘Papa, do you need anything?’ Each time, he assured them, ‘No, no, I’m all right.’ For a brief while, he seemed to be dozing; the girls, however, did not dare leave the room. It was he who, with his eyes still closed, urged them to get ready for school. He even encouraged Claire to talk to the head nun about her intention to sit for the bac. ‘The sooner, the better,’ he said.

As the girls got up, they saw their mother, holding a cup and saucer with shaking hands glide, phantom-like, through the room. She looked even more drawn than earlier. With a quick tilt of the head, she motioned for them to go.

The girls hurried out of the room. Osta Osman offered to boil eggs for breakfast.

When the girls returned from school, it was Osta Osman who met them at the door. From the look on his face, they understood.

&nbs

p; Their father had died while they were on their way home, just before the doctor was scheduled to pay his second visit of the day. Selim was only fifty-three years old, two years younger than Sir Lee Stack who would die from his wounds a few hours later.

Selim Sahli’s funeral was strictly a family affair, as he had requested. It was held at the Greek Catholic Cathedral of Darb al-Geneina, the first regular Greek Catholic church built in Egypt. Besides Letitia, Gabrielle and Claire, attending the service were his brothers Yussef, Naum and Zaki accompanied by their wives and children and his sister Warda with her daughters. His youngest brother Naguib was in Paris. Osta Osman also attended the service.

The residential center of the Greek Catholics of Cairo for much of the nineteenth century, Darb al-Geneina was the neighborhood in which Selim’s forefathers had set up house upon entering Muhammad Ali’s service as high-ranking administrative officials soon after their arrival from Syria in 1810. There, they had established themselves in grand quarters. The cathedral was built on land they had ceded.

On their way to the Greek Catholic cemetery in old Cairo, Warda – a buxom forty-year-old with a fickle husband whose frequent overseas travel she only nominally deplored – dissolved into tears. Sitting opposite her in his big Buick, her brother Yussef noted that it was the first time in a long time he had seen her shed genuine tears. Of her five brothers, Selim, the oldest, had been the one most willing to listen to Warda talk endlessly about her real and imaginary troubles.

Selim’s death had stunned his brothers and sister. They had grown accustomed to seeing him recover after each illness. When he was told over the telephone by his brother Zaki that Selim had died, Yussef’s immediate reaction was to shout, ‘But how? I was just about to call him to ask for some legal advice.’

Yussef was shaken by his older brother’s death. Even though they had had their disagreements, Yussef was deeply attached to him. Selim curbed his money-grabbing impulses. In his early forties, already rich beyond his expectations, Yussef realized that he would miss his older brother’s sobering influence. His own instinct was to grab opportunities without worrying too much about their legal or moral aspects. It was over ten years now since Yussef had concluded a deal – knowing full well that Selim would take a dim view of it – that backfired and threatened to land him in jail. The court case had been long, complicated and nerve-wracking. He had been very frightened, though he had admitted this to nobody, not even to Selim who, at the expense of his law practice, devoted most of a year to the case, and managed, in the end, to get him out of a very tight corner. Yussef felt enormously indebted to him.

In Their Father's Country

In Their Father's Country